Written for The Points Guy – April 19, 2019

On March 13, the United States and Canada both grounded the Boeing 737 MAX, among the last countries to make the move to ban the aircraft from their airspace. The decision was made, in part, from detailed “new data” outlining the final flight paths of Lion Air 610 and Ethiopian Airlines 302 that had been made available just hours before to Transport Canada and the Federal Aviation Administration.

But where did that new data come from?

It came from Aireon, the newly operational space-based aircraft tracking network that could be the most important development in locating planes since radar was invented in World War II.

Aireon is a fusion of technologies, linked together to solve a problem that has vexed the aviation industry for decades: How to accurately and dynamically track an aircraft over the 70% of the world that’s beyond the limited range of land-based radar.

The first piece of the equation is something called Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast location reporting — you’ve seen it referred to as ADS-B. Instead of air traffic controllers locating an aircraft by using a radar beam that bounces from a target every few seconds, planes with ADS-B broadcast a precise GPS-generated position report every half-second.

Among other data, the reports include flight identification, position, altitude, vertical rate of climb or descent, track, and speed.

ADS-B has been mandated by aviation regulators around the world to augment existing tracking systems. It’s been in use for years in remote locations such as Alaska and Canada’s North, with signals received by ground-based ADS-B sites. You’ve used ADS-B if you have ever used, like we do at TPG, the popular Flightradar24 aircraft tracking service, with data coming from consumer-hosted and internet-connected ADS-B receivers.

That’s where Aireon comes in.

Separately from the development of ADS-B, Iridium, the space-based global communications service, was developing in the early 2010s its new constellation of satellites, Iridium NEXT.

“We had heard some rumors of Iridium thinking about a way to put an ADS-B receiver onto the Iridium NEXT constellation,” said Rudy Kellar, Executive Vice President, Service Delivery for Nav Canada, the agency that provides air navigation services in the country. “Those kinds of opportunities don’t come along very often — somebody who’s launching a $3 billion program into low-earth orbiting space, and they have some room on 66 satellites,” Kellar said.

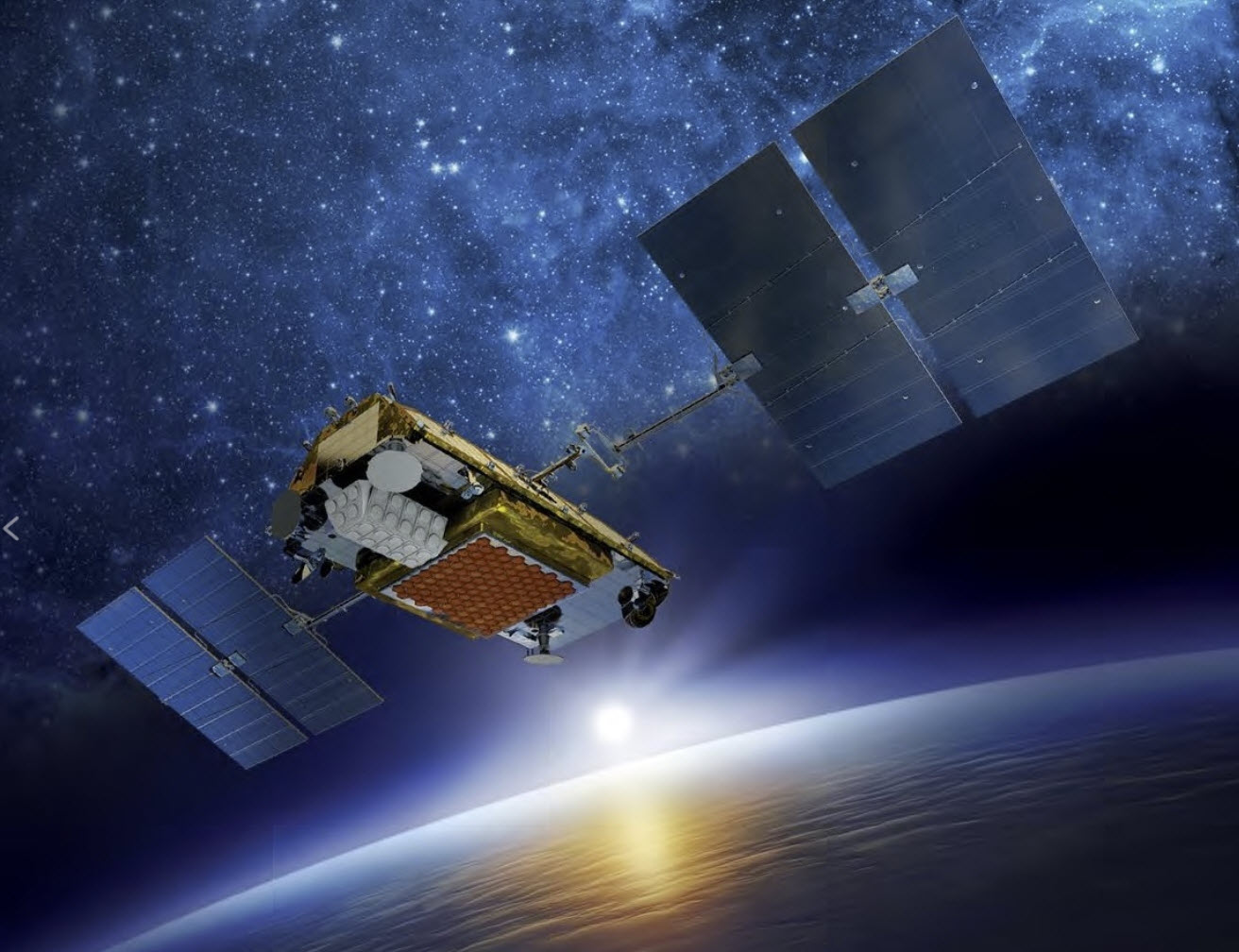

Those 66 satellites, along with nine in-orbit backups, have been launched on eight SpaceX Falcon 9 boosters. In low-earth orbit, 485 miles up, the constellation is organized in six orbital planes. The satellites zip through space, pole-to-pole, completing an orbit in about 100 minutes. Think of a giant, round necklace, with 11 evenly-spaced gems attached to it. Put that around the Earth and add five more necklaces to encircle the planet. That’s the Iridium NEXT constellation.

Each car-sized satellite is networked with its neighbors and hosts a piggyback Aireon payload that’s always facing the ground. “It’s the size of a microwave, and it kind of looks like a white Lego piece,” said Jessie Hillenbrand, Aireon’s Director of Marketing. “The data is transmitted from the aircraft and the satellite catches it. The satellite will talk with up to four other satellites at once and downlink [the ADS-B report] to the closest teleport.”

The data from thousands of aircraft is simultaneously tracked, processed and then delivered to Aireon’s clients — airlines, search and rescue organizations, regulator or air navigation service providers like Nav Canada — as quickly as a half-second after it’s received.

“When we’re fully operational we’re expecting to have 25 billion position reports per month,” said Hillenbrand. That massive amount of data will be stored in a Microsoft Azure Cloud environment.

Aireon has designed its network to accommodate the expected air traffic over the next 20 years, the expected lifetime of the Iridium satellites. The network will also be far better than existing tracking systems at following planes near the poles. Ocean-spanning flights have previously used data links that route through geo-stationary satellites, but the coverage of those satellites falls off at high latitudes.

Sitting over the equator, those satellites orbit at a speed that matches the Earth’s rotation, so that they appear to be stationary relative to an observer on the planet. That’s why the antenna on your house for a satellite-based TV service doesn’t have to move. But the satellite’s antennas can only reach so far to the north and south. That’s not the case with Iridium, and the Aireon receivers.

“As you get up or down towards the poles, you’re getting 17 overlapping satellites, which increases the availability of the service. It makes it resilient and robust, since we have more than one satellite observing an aircraft,” explained Vincent Capezzuto, Chief Technology Officer and Vice President of Engineering for Aireon.

The 66 satellites orbit in an elaborate ballet that was designed to finely-tune global coverage, and their paths are “all orchestrated in a way so they don’t collide at the North and South Pole,” said Capezzuto. 11 navigation-services agencies that cover 28 countries have signed up for Aireon’s service. Online flight-tracking service FlightAware is a partner, providing a product called Global Beacon that will redistribute Aireon’s data to airlines.

Global Beacon has been designed to meet the requirements of the International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO) aircraft tracking standards. In normal flight, a report every 15 minutes is required, but when an aircraft is in distress, the reporting interval standard drops to just one minute. That’s the requirement of ICAO’s Global Aeronautical Distress Safety System, or GADSS.

But it’s clear that even before it was fully operational, Aireon’s ADS-B tracking interval bests the ICAO requirements, as suggested by the information provided to aviation regulators on the two 737 MAX crashes. “All I can say is that we did capture the ADS-B position reports, and supplied it to the FAA, NTSB, Transport Canada, in addition to other regulators that requested that data,” said Hillenbrand.

She also described Aireon Alert, scheduled to be live at the end of April. Jointly administered with the Irish Aviation Authority, this free service for airlines, ANSPs, aviation regulators and search-and-rescue organizations will provide the last 15 minutes of tracking reports of an aircraft in an emergency.

The ability to precisely track ADS-B equipped aircraft anywhere around the globe can also speed up the critical response time for search-and-rescue efforts, a benefit that was shown during Aireon’s testing phase. “We’ve had some firsthand experience monitoring airplanes that have been in distress, in some cases that lost control, that we’ve been able to pinpoint the precise location and behavior of the airplane rate to the final point of rest,” said Nav Canada’s Kellar.

Aireon might help make mysteries like the disappearance of Malaysian Airlines MH370 far less likely. That particular case may never be solved, but it’s that missing flight that drove ICAO to develop the GADSS standards.

Now, some are thinking about having aircraft equipped with a tamperproof ADS-B transmitter to make sure that a plane’s position is always monitored. “We have proven that when the transponder is on, we can see the airplanes globally at all altitudes at many angles, when you think of the way those 66 satellites have all of the beams adjusted,” added Kellar.

Nav Canada air traffic controllers are now seeing Aireon data on their screens in Edmonton Centre, covering Canada’s North and the High Arctic. Trials are also underway tracking aircraft flying the North Atlantic.

Airlines are expected to see additional operational efficiencies from Aireon’s service, and passengers flying over the North Atlantic might enjoy a smoother flight. Half a million flights per year follow the Organized Track System (NA-OTS), flying what are daily-defined aerial highways between North America and Europe.

“With the track operation today we go through a lot of operations with turbulence,” said Nav Canada’s Kellar.

“Lack of predictability allows us to not necessarily do a lot of movement off the tracks or the [assigned] altitudes. Whereas now with the [Aireon] surveillance, as we progress through the trial, we’ll be able to certainly allow a lot more flexibility for the airlines and their passengers to move up or down out of turbulent airspace.”